When it comes to assessing fabrics, the world of #menswear has been hindered by a kind of "folk reasoning" which tends to oversimplify things in assessing quality. Let me give you a couple of examples I've observed. The first is an erroneous tendency to assess fabric quality and performance through a single variable such as hand feel. The other is the almost exclusive use of subjective opinion to assess quality and performance without any data (or very limited data).

The first tendency rests on the belief that one can discern fabric performance through hand feel or hand manipulation of fabric. A common "test" described on forums is grabbing or pinching part of the fabric and observing if wrinkling occurs. Another test I recall reading on a discussion forum thread also involved pinching a fabric and observing the ability of the pinched portion to maintain its stiffness. There are quite a few flaws in these "tests" although they are weakly related to legitimate tests for wrinkle recovery and drape.

Standardized industry tests do exist but the ones described above sadly do not qualify. If only it were that easy! In textiles, there are two governing industry bodies. The one most relevant for this discussion is ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials). More specifically, the standard performance spec for menswear is D3780-02 aka "Standard Performance Specification for Men's and Boys' Woven Dress Suit Fabrics and Woven Sportswear Jacket, Slack and Trouser Fabrics".

I would hypothesize that men's suitings and jacketing produced by most reputable mills would pass ASTM D3780-02 in the two most common tests of textile durability - breaking strength and abrasion strength. If true, there are clear implications for #menswear. For instance, stop speculating or fixating on whether Harrisons or Lesser 11oz worsted or Drapers or Halstead mohair is more durable. I think the likely answer is that both will probably meet or exceed established quality standards. I think the more nuanced question is which fabric best meets the aesthetic requirements of your end use.

I say this because most end-users are not properly equipped or trained to test for quality or performance. But they can assess the aesthetic qualities like hand feel. Of course, the danger is that #menswear aficionados extrapolate quality and performance characteristics from the aesthetic features of a fabric.

So who is qualified and incentivized to test for textile quality and performance? That would be the industry itself, specifically internal textile quality management groups at large vertically integrated textile manufacturers or third party testing labs commonly utilized for such purposes.

The textile industry has been steadily consolidating into fewer and larger producers, which has its pros and cons. One could argue smaller mills and weavers wouldn't be able to afford the costs of quality testing and management. Either way, the industry views a performance category like durability from a minimum threshold perspective - i.e. whether its fabrics can meet the ASTM performance spec in certain areas like breaking strength or abrasion strength - rather than from a comparative perspective (i.e. does my mohair perform better than my competitor's mohair?).

Yet #menswear enthusiasts love to argue whether English mill X produces more "durable" fabric than mill Y, often with no data on hand. Therein lies the dilemma. Even without real data, this doesn't stop enthusiasts from filling pages of discussions threads with speculation based on personal experiences and anecdotes.

At best, these end-users rely on a very loose application of what is known formally as "wear testing". While it has advantages, wear testing has a key weakness - lack of comparability of results. Since every wearer will treat and use the product differently, wear testing has low precision (i.e. poor reproducibility of results in a larger sample) despite high accuracy in the individual case.

What works better is materials testing or end-use performance testing as exemplified by ASTM D3780-02. It's better because it's based on data collected under more controlled conditions. So let me present some data based on five fabrics on which I conducted breaking strength and fabric weight tests to see (a) whether the ASTM minimum threshold for strength was met (b) the fabric weighed close to the advertised weight.

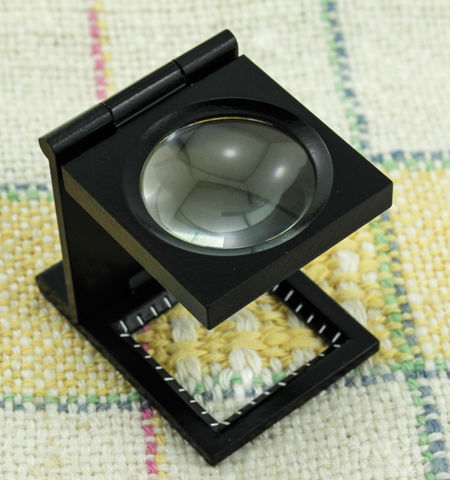

As I mentioned before, strength and abrasion are the two most common tests in durability testing. The testing involves a grab test in which a sample fabric strip is held on both ends and stretched until it fails (see demonstration video below). If I had enough time, I would have conducted the standard Martindale or Taber abrasion test on my samples. I also would have had run three sets of test strips. In other words, for each fabric, I would have cut three strips each in the warp and fill direction instead of just one warp and one fill test strip for each fabric.

The five fabrics tested were: Zegna 15 milmil 15 moss glenplaid wool jacketing (15 micron fibers), Drapers Super 150s gunclub jacketing, Scabal Vivaldi Four Seasons Super 120s 10oz glenplaid suiting, Minnis 2-ply fresco and a (likely Italian) dogtooth linen suiting or jacketing. Below is a photo of the sample test fabrics.

![Breaking strength test samples]()

So how did these fabrics do? I've ordered the results based on their breaking strength. For worsted and cotton fabrics, the ASTM D3780-02 spec establishes a tensile requirement of 40 lbf for suits and trousers and 30 lbf for jackets. All the fabrics passed the breaking strength test for suits, trousers and jackets except for one fabric (Scabal for suit/trouser use):

Test results - maximum loads in warp and fill directions (lbf) and fabric weight (per linear yard)

![Minnis fresco breaking strength test results]()

The data reveals a few interesting things (although I would of course caution against excessive generalization based on one test sample from each fabric):

The first tendency rests on the belief that one can discern fabric performance through hand feel or hand manipulation of fabric. A common "test" described on forums is grabbing or pinching part of the fabric and observing if wrinkling occurs. Another test I recall reading on a discussion forum thread also involved pinching a fabric and observing the ability of the pinched portion to maintain its stiffness. There are quite a few flaws in these "tests" although they are weakly related to legitimate tests for wrinkle recovery and drape.

Standardized industry tests do exist but the ones described above sadly do not qualify. If only it were that easy! In textiles, there are two governing industry bodies. The one most relevant for this discussion is ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials). More specifically, the standard performance spec for menswear is D3780-02 aka "Standard Performance Specification for Men's and Boys' Woven Dress Suit Fabrics and Woven Sportswear Jacket, Slack and Trouser Fabrics".

I would hypothesize that men's suitings and jacketing produced by most reputable mills would pass ASTM D3780-02 in the two most common tests of textile durability - breaking strength and abrasion strength. If true, there are clear implications for #menswear. For instance, stop speculating or fixating on whether Harrisons or Lesser 11oz worsted or Drapers or Halstead mohair is more durable. I think the likely answer is that both will probably meet or exceed established quality standards. I think the more nuanced question is which fabric best meets the aesthetic requirements of your end use.

I say this because most end-users are not properly equipped or trained to test for quality or performance. But they can assess the aesthetic qualities like hand feel. Of course, the danger is that #menswear aficionados extrapolate quality and performance characteristics from the aesthetic features of a fabric.

So who is qualified and incentivized to test for textile quality and performance? That would be the industry itself, specifically internal textile quality management groups at large vertically integrated textile manufacturers or third party testing labs commonly utilized for such purposes.

The textile industry has been steadily consolidating into fewer and larger producers, which has its pros and cons. One could argue smaller mills and weavers wouldn't be able to afford the costs of quality testing and management. Either way, the industry views a performance category like durability from a minimum threshold perspective - i.e. whether its fabrics can meet the ASTM performance spec in certain areas like breaking strength or abrasion strength - rather than from a comparative perspective (i.e. does my mohair perform better than my competitor's mohair?).

Yet #menswear enthusiasts love to argue whether English mill X produces more "durable" fabric than mill Y, often with no data on hand. Therein lies the dilemma. Even without real data, this doesn't stop enthusiasts from filling pages of discussions threads with speculation based on personal experiences and anecdotes.

At best, these end-users rely on a very loose application of what is known formally as "wear testing". While it has advantages, wear testing has a key weakness - lack of comparability of results. Since every wearer will treat and use the product differently, wear testing has low precision (i.e. poor reproducibility of results in a larger sample) despite high accuracy in the individual case.

What works better is materials testing or end-use performance testing as exemplified by ASTM D3780-02. It's better because it's based on data collected under more controlled conditions. So let me present some data based on five fabrics on which I conducted breaking strength and fabric weight tests to see (a) whether the ASTM minimum threshold for strength was met (b) the fabric weighed close to the advertised weight.

As I mentioned before, strength and abrasion are the two most common tests in durability testing. The testing involves a grab test in which a sample fabric strip is held on both ends and stretched until it fails (see demonstration video below). If I had enough time, I would have conducted the standard Martindale or Taber abrasion test on my samples. I also would have had run three sets of test strips. In other words, for each fabric, I would have cut three strips each in the warp and fill direction instead of just one warp and one fill test strip for each fabric.

The five fabrics tested were: Zegna 15 milmil 15 moss glenplaid wool jacketing (15 micron fibers), Drapers Super 150s gunclub jacketing, Scabal Vivaldi Four Seasons Super 120s 10oz glenplaid suiting, Minnis 2-ply fresco and a (likely Italian) dogtooth linen suiting or jacketing. Below is a photo of the sample test fabrics.

So how did these fabrics do? I've ordered the results based on their breaking strength. For worsted and cotton fabrics, the ASTM D3780-02 spec establishes a tensile requirement of 40 lbf for suits and trousers and 30 lbf for jackets. All the fabrics passed the breaking strength test for suits, trousers and jackets except for one fabric (Scabal for suit/trouser use):

Test results - maximum loads in warp and fill directions (lbf) and fabric weight (per linear yard)

- Minnis : 59.7 lbf, 80.5 lbf, 9.5 oz

- Drapers: 67.1 lbf, 60.3 lbf, 8.2 oz

- Zegna: 57.4 lbf, 55.2 lbf, 9.7 oz

- Linen: 56.1 lbf, 48.8 lbf, 7.8 oz

- Scabal: 61.0 lbf, 36.8 lbf, 7.5 oz

The data reveals a few interesting things (although I would of course caution against excessive generalization based on one test sample from each fabric):

- The tested fabrics, which are from well-known Italian and English mills, generally met or exceeded the breaking strength for the most common applications for these fabrics (suits, trousers, jackets).

- The only possible exception is the Scabal which came in just under the 40 lbf minimum at 36.8lbf in the fill direction, which is also generally the weaker direction of most fabrics. As this is a single test strip on one section of a fabric length the result is not conclusive but intriguing and suggestive. More test samples would be needed to determine if this is indeed an issue. But among other things, the Scabal length I purchased from a local fabric shop could have been a variation from their final production run as I noticed the selvedge seemed a bit unusual.

- A Super 150s fabric in the right weave, finish and yarn quality (i.e. Drapers) can easily exceed the ASTM strength test for suits, jackets and trousers, even as a lightweight fabric. So much for the anti-Supers bias that many (including formerly myself) adhere to.

- The top performer was the Minnis 2-ply fresco which bested the breaking standard by 49% and 101% respectively in the warp and fill direction. Clearly, the 2-ply yarns (as well as twist) play a key role in enhancing fabric strength, although they appear to be used just in the fill direction.

- In terms of weight, the only advertised weights I have are for the Minnis and Scabal. The Minnis measured very close to its published weight of 280-310g. The Scabal fell a bit short of its advertised 10 oz, which, as described above, may or may not indicate a defect.

addresses the popular notion that a young, dynamic and hatless JFK hammered in the final nail in the coffin of hat wearing. These are certainly plausible explanations but they all suffer from a severe lack of data, evidence and supporting material.

addresses the popular notion that a young, dynamic and hatless JFK hammered in the final nail in the coffin of hat wearing. These are certainly plausible explanations but they all suffer from a severe lack of data, evidence and supporting material.